This is the first instalment in a series of photostories illustrating the history and decline of Colombo’s “adult film” cinemas. The popularity of these cinemas peaked in the 1980s and ’90s, as imported pornographic movies proved popular with local audiences and guaranteed profits for film halls. With time, increased social conservatism and the widespread availability of “adults–only” content online sent these cinemas teetering on the brink of dissolution, where many still remain.

We almost walk right past the entrance to the New Ricky Cinema, a nondescript, narrow corridor on Parsons Road in Colombo 2. A young woman stands behind a selection of lukewarm short eats displayed inside a glass box on the threshold, and a few lone diners pepper the small metal tables and chairs placed here and there along the entryway. Further down, the walls are lined with cinema chairs in shades of red, the once–plush upholstering now worn, torn and dusty.

Before the building was renovated into a theatre, it functioned as a meeting hall that belonged to the Government Secretariat Association. “Some people say it was used as a torture camp during the JVP insurrections, that people were murdered here,” says current owner Nimal Kularatne. “It was completely abandoned when we bought the place.”

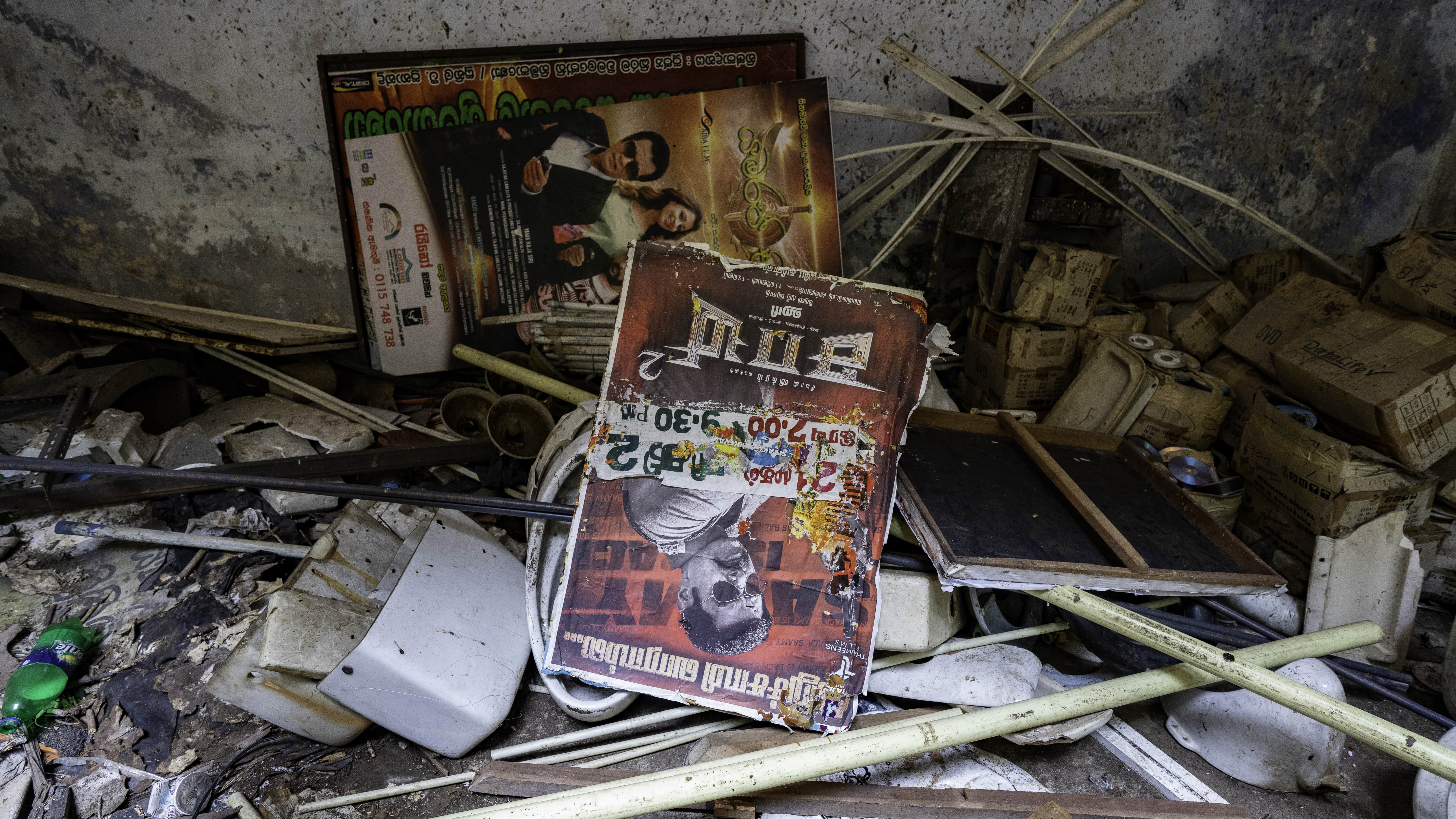

The building is barely hanging on. The structure encloses an open area at its centre, where debris piles up in small heaps, a jumble of ruins burying from view nearly all traces of the ground beneath. The business is not doing much better, according to Kularatne. “We barely have patrons coming in. I didn’t even bother going to see how many tickets we sold this morning,” he says. Running at a loss of Rs. 300,000 per month since the onset of COVID–19, Ricky’s future looks grim.

The cinema used to comprise two halls. Ricky 1 screened and continues to screen movies in Sinhala and Tamil, many of them made locally. Ricky 2, a separate hall located behind the first, is now abandoned, a scattering of scrap metal and movie posters blocking the entrance. “We used to show adults–only films in Ricky 2,” says Kularatne, “but we don’t show those types of films anymore.”

“I believe the first adults–only film was distributed by the National Film Corporation in the ’90s,” says Kularatne. “After that, other companies started to bring them [to the country].” The films’ popularity with audiences led to the production of Sinhala-language adult films, although Kularatne notes, “Regardless of the language of the movie, be it Sinhala, English or Tamil, there would be people to watch it — couples, individuals, mostly men.”

In addition to their crowd–pleasing appeal, adult films proved to be a cost–effective choice. “The duration is short — a maximum of one hour or an hour and fifteen minutes. That saves a lot on electricity,” explains Kularatne. They also save on advertising: “There’s no need to market them, no need for boards, banners or posters. People come to watch them out of habit.” Even now, he says, despite Ricky 2 having shut down three years ago, former patrons stop by to inquire about whether it still screens adult films. “When we tell them that the hall is not there anymore and direct them towards the movies we showcase here [at Ricky 1], they’re not interested.”

Following a political backlash as a result of public pressure in the period between 2005 and 2010, Kularatne says many cinemas stopped screening pornographic content. “There is no written law against it. The censor board will approve anything, we just have to request it,” explains Kularatne. “But we, as a collective of film hall owners, have decided that we will not screen adults–only films as they had a major impact on Sinhala cinema.”

In spite of waning profits and deepening losses, Kularatne and other cinema owners have remained steadfast in this mission to protect and foster the local film industry. Aale Corona, a recently released Sinhala–language pornographic film based on the premise of the ongoing pandemic, flopped following the refusal of many cinemas, including Ricky, to screen it. “A couple of other film halls managed by the [film] corporation screened it, but a lot of us refused,” Kularatne says. “It ran for less than a week and it gained no income whatsoever.”

Despite the fact that it was its run–down counterpart that was renowned for illicit features, Ricky 1 is also seemingly built for privacy. The rear of the balcony is lined with box seats, and at least two couples emerge from the small, secluded alcoves at the end of the morning show. Built to accommodate 850 people, Ricky 1 is the largest hall in the country and features the largest screen, according to Kularatne. Still, only six or seven people exit the cinema as the credits roll on the 2021 action thriller Colombo.

Although adults–only content is now widely available on the internet, the phenomenon of watching softcore porn on the big screen in a public setting remains a sought–after experience by Sri Lankans of a certain generation and persuasion. “A lot of expenses would reduce if we opted to screen these movies. There will be at least 50 people for a show, so there would be a considerable income,” reasons Kularatne. “But we have stopped showing them with the intention of saving Sinhala cinema.”